Keeping Clean

By Elizabeth Shearon

Edited by Assistant Public Defender Meigan Thompson

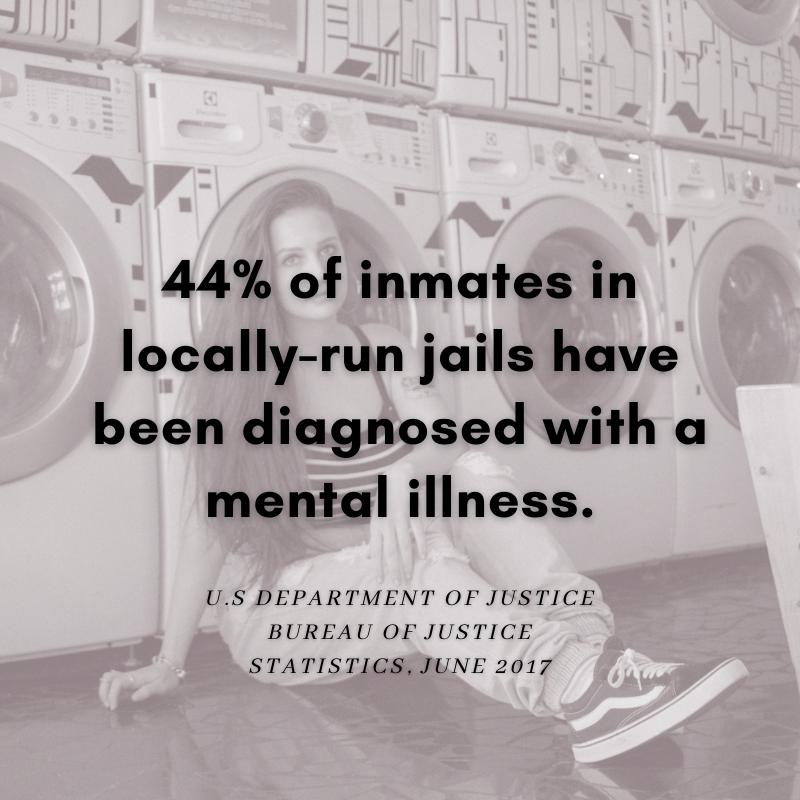

A few years before the arrest happened, Amy was diagnosed with a mental health illness. Her diagnosis stemmed from a series of traumatic events that she had experienced as a child. Having never received treatment to cope with the emotional weight that she carried, Amy struggled to maintain the relationships in her life. It was challenging. Amy’s employer let her go in December of 2019. Soon thereafter, Amy’s parents asked her to leave their home. For the first time ever, Amy was homeless.

At first, Amy lived in her car. The only food she had were granola bars and a jar of peanut butter that she took before leaving her mother’s house. After her car was damaged beyond use, Amy was out on the streets with no shelter of her own, sleeping on empty porches in Midtown and doing everything she could to keep warm during the cold and rainy winter months. “After two to three weeks, I couldn’t take it.” said Amy.

One January afternoon, Amy was arrested by Memphis police officers after she left a retail store without having paid for a winter jacket and undergarments. When questioned, Amy told the police that she was homeless and needed the clothing to survive. As the police officer prepared her arrest ticket, he realized that Amy had an outstanding warrant for her arrest on a separate theft charge that her parents had filed against her the previous month. For both of these offenses, Amy was transported to Jail East – a jail for women in Shelby County – and incarcerated on felony and misdemeanor charges.

At Jail East, Amy was put to work in the laundry room. She would gather dirty linens from different areas of the jail, bring those dirty linens to the laundry room, assist in the laundering of those linens, and help to deliver those linens around the jail. Amy also worked in the kitchen and brought food trays to women all over Jail East.

“From the beginning, Amy was very clear with me that she wanted to enroll in treatment so that she could address her mental health issues.”

In early February, the court appointed Assistant Public Defender Carolyn Sutherland to represent Amy in her criminal cases. “From the beginning, Amy was very clear with me that she wanted to enroll in treatment so that she could address her mental health issues,” said Public Defender Sutherland. “Being that I am also an attorney in the Mental Health Court program, I spoke with her about Mental Health Court. Initially, however, Amy preferred to remain at Jail East because she had a routine and felt she could obtain some treatment there. Her preference to receive community-based treatment through Mental Health Court didn’t come until later.”

By mid-March, news of the coronavirus had reached Jail East. Amy’s access to information about the disease was sporadic and left her feeling uncertain about the nature of the illness. She mostly heard about the coronavirus “through the grapevine,” only getting information from security officers who were willing to share what they knew or other women who had learned about it through phone calls with family and friends. “Certain pod officers were more dramatic than others but some seemed to have a vow of silence to not really tell us anything,” Amy said. All Amy knew was that people were dying in the thousands and that the disease was spread through contact with infected people and the particles expelled by coughing, sneezing, and even just talking.

As days went by, Amy grew increasingly worried that the risk of her exposure to the coronavirus was inevitable. Her work detail required her to continue traveling to different areas of the jail – from carrying armfuls of dirty sheets to handling people’s food – and Amy was not given any protective equipment to wear. While deputies around the jail wore masks and gloves, and enjoyed the luxury of social distancing, Amy had to traverse the facility without any masks or gloves. “I was constantly going out to different pods to deliver clothes, touching incarcerated people and breathing in soiled linens from all around the south side, and being exposed to different officers.” said Amy.

Because of the coronavirus, Jail East stopped providing the classes that Amy had participated in to address some of her mental health issues. “Being in jail in those conditions with a pandemic going on made me want to get out and not feel so helpless – I didn’t want to die in there,” Amy said.

“By April, defenders in Mental Health Court were pushing to get all of our eligible clients out of jail and into treatment centers. Many of the treatment centers in Shelby County were not accepting new patients, particularly those from jail, due to the coronavirus.” said Public Defender Sutherland. “We talked to Amy and she made it clear that she wanted to receive community-based treatment through Mental Health Court. Fortunately, we were able to make that happen for her.”

In mid-April, Amy was placed in a private treatment facility where staff and administration did their best to follow safety guidelines set by the CDC. For the first time, Amy was finally able to feel safe because the facility incorporated social distancing, required face masks, and even conducted regular COVID-19 testing. Thankfully, when Amy went home in June, after having completed her stay at the treatment facility, she was not nervous. “They were so diligent.”

“Without Mental Health Court, it’s very likely that Amy would have been unmedicated and back on the streets as a convicted felon, serving out her sentence on probation,” says Public Defender Sutherland. “However, because Amy was able to receive inpatient mental health treatment, she has thrived, and been able to continue her treatment at home. We expect her to graduate from the Mental Health Court Program early next year with no conviction on her criminal record.”

Now equipped with the knowledge of how to manage her mental health issues, Amy looks forward to the next chapter of her life. When she does reflect on her time at Jail East, however, she wonders how it was possible that she remained covid-free. It weighs on her greatly to think about how many women were not so lucky.

*In order to protect our client’s identity, the client’s name has been changed.

Contributing Writer

Elizabeth Shearon, JD

Tulane University

I wanted to become involved in the Humanity Project because I feel it is absolutely vital that, as public defenders, our advocacy extends outside of just our interactions in court and with our clients. In the case of the Humanity Project, we were presented with a unique opportunity to take clients’ stories and experiences, and use them to let the community know what its members are going through while incarcerated. Changes at a structural level begin with widespread awareness, and the Humanity Project has been a great way to make sure our clients’ voices are heard.